Part 4 - Lighting and Using Flash in Butterfly Photography

The earlier articles in this series in Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 dealt with the variety of photographic equipment that can be used for butterfly photography, the types of magnification devices and the typical settings on a DSLR system that a butterfly photographer uses. We also discussed the interrelationship between the ISO, aperture settings and shutter speeds when taking a photo.

In this week's article, we take a look at how different lighting conditions can "change" a butterfly's appearance and how lighting can be used to enhance your shots. In the macro photography genre, which butterfly photography falls under, the use of artificial lighting is often quite critical. One of the main issues with macro and butterfly photography is the problem of light fall off. As magnification increases, light decreases. This is even more critical as a photographer needs to use a small aperture to get better depth of field for sharp shots, and has to shoot a butterfly under shade.

Macro combo on a tripod. Ideal for non-skittish subjects. For shooting butterflies, tripods tend to be more of a hindrance especially when tracking butterflies that flit from flower to flower rapidly or bashing amongst the thick undergrowth to get at a perched butterfly.

Purist macro photographers have always advocated the use of a tripod for doing close-up work. Shooting from a stable platform allows the photographer to focus accurately on the subject and use appropriate settings to get the sharpest shot and optimal exposure, without having to deal with motion blur. This is fine, if you have subjects that are not particularly skittish and only stop for a fleeting moment on a flower to feed!

Butterfly paparazzi all shooting handheld with an external flash mounted on the camera

Butterfly photographers often have to contend with alert subjects, those that flutter continously for hours on end, and constantly change positions even when they stop to feed. Trying to set up a tripod with sophisticated off-camera flash combos to shoot constantly moving butterflies is at best impractical, and at worst, an exercise in futility! Hence many butterfly photographers train themselves to handhold their shots, as they chase a butterfly and their minimal equipment allows them the flexibility to quickly adjust their positions to capture their subjects without spooking the butterfly off.

Using Flash in Butterfly Photography

We have often been asked if it is better to do butterfly photography in natural lighting without the use of a flash. Whilst it is certainly possible to photograph a butterfly with available natural lighting, conditions frequently change that make it challenging to get a well-exposed shot or capture the true colours of a butterfly's wings. This is where the use of a "portable sun" comes in handy. A good DSLR system comes with technically-advanced dedicated flash systems that make flash photography a breeze.

A butterfly shot in bright sunshine with a flash in front curtain sync. The flash illuminates the subject butterfly accurately, but ignores the background, rendering it almost totally black. Whilst the contrast between the subject and background makes it an interesting shot, it does not appear "natural" and does not accurately reflect what the actual environment looked like when this shot was taken.

Let us start with the typical settings of using a flash in general photography, and the settings that are required in butterfly photography. Most normal flash photography situations employ the use of the front sync (or 1st curtain sync) where the flash fires immediately after the shutter opens. In very simple terms, the camera flash illuminates the subject and exposes it accurately. In butterfly photography, this gives results that appear like a butterfly was shot at night, particularly when the surroundings in which the butterfly was shot is in shade or dimly lit. This is generally not how you would perceive a butterfly in its natural environment.

A butterfly shot in very dim lighting on the shaded forest understorey. The 2nd curtain flash helps to even out the ambient lighting with an extra fill-flash light to create a pleasing balanced exposure of the butterfly against its background

This is where the rear sync mode (also called the 2nd curtain) comes into play. If the flash fires right before the shutter starts to close to end the exposure, this is called 2nd curtain sync (or rear sync). Essentially, when one uses the rear sync mode, the camera exposes for the whole scene before the flash fires just as the shutter closes. This allows the flash to perform as a "fill-flash" that exposes the subject just before the shutter closes. The result is a more evenly exposed shot of the butterfly with a well-lit background, appearing more natural.

A butterfly shot in bright sunshine with the flash illuminating the subject against a bright background

The following diagrams below show how to set the camera to Rear (or 2nd) curtain sync in Canon and Nikon DSLR and respective Speedlight systems. For other brands, please refer to your camera manuals on how to set these flash functions.

A butterfly shot in bright sunshine with the flash illuminating the subject against a bright background

The following diagrams below show how to set the camera to Rear (or 2nd) curtain sync in Canon and Nikon DSLR and respective Speedlight systems. For other brands, please refer to your camera manuals on how to set these flash functions.

Setting 2nd Curtain flash sync on a Canon camera body. This controls the built-in flash

Setting the 2nd curtain flash sync on Canon Speedlight external flash

For Nikon systems, change the flash settings to Rear (2nd curtain) flash sync until the command screen shows SLOW/REAR under flash mode

Macro enthusiasts tend to use a myriad of accesories to mute the harsh effects of a direct flash - from "softboxes", putting in tissue in front of the flash, and a whole host of creative and customised flash attachments. Others use different flash brackets to take the flash off-centre and off camera to move the flash off axis with the lens. Some advocate the use of ring lights and specialised macro flashes.

A typical "softbox" flash diffuser that some macro photographers use. Large enough to scare off butterflies in the field

Twin macro flash mounted off camera with adjustable brackets. Good for creative lighting in macro work but absolutely impractical for shooting butterflies out in the field! And guaranteed to scare off butterflies with this "monster-like" contraption, long before you can get anywhere near them!

From our experience, shooting butterflies requires a lot of flexibility and ease of freedom of movement in the field. Attaching large devices to your flash will probably scare off the butterflies long before you can get close enough to shoot them. Furthermore, the effect of trying to diffuse the light from the flash is less critical on a two-dimensional subject like butterflies, as compared with beetles with shiny reflective carapaces or a fat (and very 3D) caterpillar.

A typical butterfly shooter's handholding stance with an external flash mounted directly on the camera

Hence, keep it simple. Most of us shoot with the external flash mounted directly on the hotshoe of camera. Canon users don't even put the diffuser on their flashes, preferring to shoot direct and let the ETTL technology do its work. Nikon Speedlights tend to be a bit more harsh and having the diffuser cup on the flash usually gives better results. Whilst purists would argue otherwise, the thousands of butterfly photos featured on ButterflyCircle's online sites bear testimony to the techniques used by butterfly photographers.

However, let us get back to the question of why use a flash in full bright sunshine? The effects of strong and harsh sunlit conditions in the field can be mitigated with the fill-flash effects of the rear curtain sync function. The fill-flash brings out areas of the butterfly's wings that may be in shadow, and evens out the dark/light contrast in bright sunshine.

When the subject is in shade and the background is bright, the camera's multi-pattern metering mode may average the exposure across the frame and render the subject butterfly slightly under-exposed. The rear curtain sync mode will then add in a little fill light to expose the subject and bring it out from under the shadow, giving the final result a more well-balanced exposure against a bright background.

Making use of natural backlighting to create an interesting shot. The light filters through the translucent wings of the butterfly, creating an artistic shot

Having explained the benefits of using the rear curtain sync flash mode in butterfly photography, there are opportunities in the field that make use of ambient lighting conditions to deliver a creative and eye-pleasing result. For example, back-lit situations can be used to create artistic compositions that accentuates the "translucency" of a butterfly's wings.

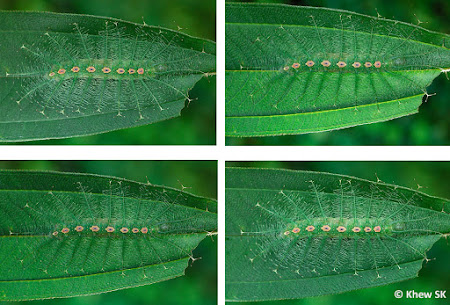

Same subject, different positions of two light sources create different moods and expressions that highlights different details and aspects of the subject

Off camera flash positions can also be utilised to create different moods and artistic expressions of the subject, if an opportunity presents itself where a subject (like this caterpillar) is in a cooperative mood and stays still enough for the manipulation of the light source around it.

Hence, in butterfly photography, whilst there are general guidelines to getting an eye-pleasing shot, there are no fixed techniques or answers to every single shooting situation. The key is to explore, experiment and execute your techniques and see which ones work best to deliver the outcomes that satisfies you most!

Hence, in butterfly photography, whilst there are general guidelines to getting an eye-pleasing shot, there are no fixed techniques or answers to every single shooting situation. The key is to explore, experiment and execute your techniques and see which ones work best to deliver the outcomes that satisfies you most!

Text by Khew SK : Photos by Sunny Chir, Chng CK, Antonio Giudici and Khew SK

5 comments:

Thank you so much for a concise and informative piece.

Thanks Antony. Glad you found the article useful. :)

Not sure about this. Surely with a static subject, there is no difference between rear-curtain and front-curtain sync, the results will be identical. With a moving subject, you'll see a motion blur trail behind the subject, which appears more normal, than a trail in front of the subject which you'll see with front-curtain. No problem leaving the camera in rear-curtain sync all the time, but the only occasion on which you'll see any difference is with something like the Graphium swallowtails, where you'll see motion blur from the moving wings in a more natural way. The "midnight" effect from an under-exposed background is a different issue.

A reasonably lucid explanation here:

http://www.scantips.com/lights/flashbasics5.html

Nice article and info. But I always thought exposure timing is set when we press the shutter release button. Hence whatever amount of light falls on the subject makes no difference to shutter speed after we press the button. Hence rear and front sync should give same results on static subject

Nice article and info. But I always thought exposure timing is set when we press the shutter release button. Hence whatever amount of light falls on the subject makes no difference to shutter speed after we press the button. Hence rear and front sync should give same results on static subject

Post a Comment